UCI’s Cybersecurity Policy & Research Institute (CPRI) recently partnered with the Atlantic Council and the Marine Corps University Foundation (MCUF) to provide a half-day cyber simulation event, approximating adership decision-making during a crisis with cyber actions. Event participants were notified of cyber activity related to an “escalating crisis” with a rival nation. They had to choose between a number of options to de-escalate the crisis, conduct a proportionate response or escalate the situation. They then had to recommend a coordinated response, ranging from “publicly call for third-party mediation” to “use exploit chains to erode rival military navigation.”

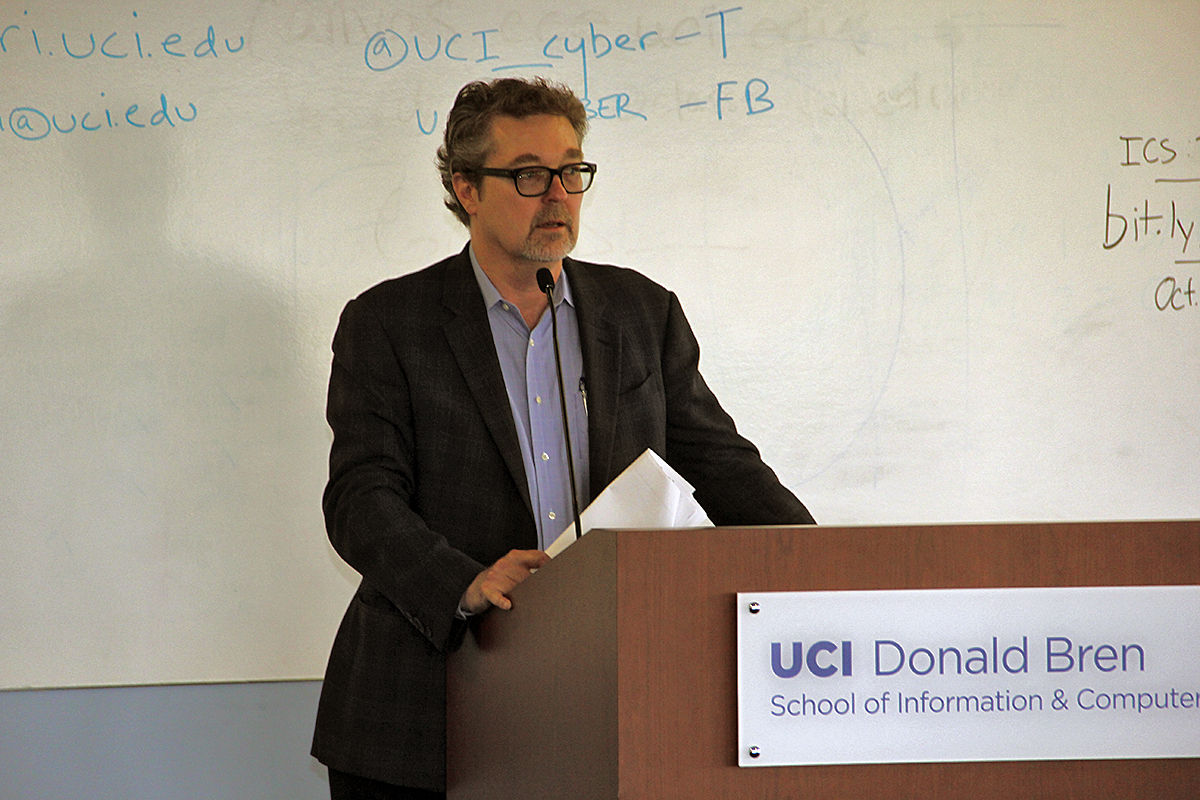

“Having participated in a number of actual national security crisis meetings,” said CPRI Executive Director Bryan Cunningham, welcoming everyone to the event, “I can tell you that the [scenario] is pretty accurate.” The former White House lawyer and adviser warned the participants prior to the exercise, “You will find that you have not anywhere near enough information and not anywhere near enough time, and that is how reality works in many crisis situations.”

Professor Brandon Valeriano, Donald Bren Chair of Armed Politics at the United States Marine Corps University, then explained that the simulation was part of a long-term project to understand how cyber conflict works. “A lot of doctrine and strategy is guesswork. The lack of understanding of the rules of the road is a problem.” Consequently, the Atlantic Council and MCUF are conducting 20 to 30 of these simulations around the world — including in Zurich, London, Scotland and possibly even Russia and China. The goal is to learn how different actors in each country view thresholds for escalation in a major conflict involving cyberattacks.

As Cunningham explains, “there is no empirical data on how different cultures will respond in terms of signaling an escalation in cyberwarfare.”

The Culture of Signaling

“In traditional conflict doctrine and practice of countries in war, or in a run-up to war, a whole culture of signaling has developed,” says Cunningham. For example, sending a ballistic missile submarine out to sea can serve as a deterrent in traditional warfare. “There’s a common understanding of levels of escalation.”

“With cyberspace,” he notes, “there’s nothing close to an agreement.” Cunningham fears that this lack of understanding could have significant consequences. “As a result, there is much greater risk in terms of escalating to actual warfare than there is with nuclear weapons or conventional weapons, because everybody is messing around with it but nobody knows the effects or at what level individuals feel they have the right to respond.”

During the event’s simulation, participants were broken out into four groups of roughly 10 people each. “The biggest surprise to me,” says Cunningham, “was how much disagreement there was between the groups about the necessity for accurate, provable attribution of a cyberattack.” This observation reflects CPRI legal research to determine how much certainty is enough in various areas of law — criminal, civil and international — to successfully identify an attacker.

Furthermore, it’s important to note the difference between “accurate” and “provable” attribution. While a government’s intelligence sources and methods might determine the attacker with a very high degree of certainty, “proving it on the world stage — at the United Nations or NATO — is a different story,” says Cunningham. “You might not want to reveal your sources in order to prove it.”

For the simulation, he expected that the more the groups perceived the attribution to be credible, the more likely they would be to act aggressively. However, people across the board showed reluctance. “I was surprised, overall, at how cautious people were about escalating, particularly as this was only a simulation,” says Cunningham.

According to participant Nemi George, senior director of information security & IT governance at Pacific Dental Services, “the exercise was helpful in showing how difficult attribution is in real-world scenarios.”

CPRI Cybersecurity Fellow April Sather, who also participated in the event, adds that “the time pressure was pretty intense. You have to quickly make decisions, under major uncertainty, that have huge consequences, and I think that might be why they said, ‘I’ll take a lighter touch here, because I don’t know if I’m doing the right thing.’”

The simulation achieved its two main goals: While Dr. Valeriano gathered data about stakeholder behavior during cyber conflicts to gain a better understanding of cyberwarfare decision making, the participants gained an understanding of some of the governmental activity and potential consequences of nation-sponsored cyberattacks.

The High-Stakes Game of Cyber Conflict

For George, the exercise “showed what little information and time decision-makers in situation rooms have to make critical decisions, often with life or death consequences.” He wasn’t the only participant to recognize the significance of this decision-making process.

“A number of participants from the business world told me that it’s really valuable for them to have some insight into how governments make these kinds of decisions,” says Cunningham. This understanding is important because much of the critical infrastructure likely to be targeted in a major nation-sponsored cyberattack is in the hands of the private sector.

The simulation started with a scenario in which a company (in a country allied to that represented by the participants) was attacked with ransomware, so Cunningham asked the group, “if this attack happened to your company, and you had some reason to think that it was not just an attack against you, but also was a major national security threat, would you report it?” Only a handful of people raised their hands, which came as no surprise to Cunningham given his experience as a cybersecurity lawyer. However, this common reaction creates a significant security risk.

This gets back to the question of signaling. If companies don’t report foreign attacks on our infrastructure, and the attacked government does not respond — the attacker might not realize that a signal wasn’t received. “So they might think we ignored it, and we’re weaker than they thought or won’t stand up to them, risking dangerous escalation,” says Cunningham.

He thus views these exercises as a way to bridge the gap between industry and government, and even between information security officers and lawyers. “From the standpoint of a chief information security officer (CISO), in many cases, you don’t care who is attacking you. You just want to stop the attack and identify and remediate vulnerabilities,” he explains. A prosecutor, on the other hand, will need evidence of the launched attack, and a national government might well need to prove attribution in order to justify a counterattack. So, CISOs need to understand why gathering evidence is important, while government officials must recognize that in the middle of a crisis, CISOs will have different priorities. “It’s an educational function [to] try to get all the different groups of people to understand each other better.”

Sather adds that this type of experience “might help businesses view cyber infrastructure as a shared asset whose compromise could end up having public safety implications.” She goes on to explain that, “after this experience, one could argue that not reporting attempted breaches is analogous to suspecting someone may have poisoned the water supply, but not sharing that information. Providing discreet, even anonymous ways for businesses to share attack intelligence is critical.”

George came away from the event feeling that “organizations — nation states, companies, etc. — need to focus on tools, techniques and technology to increase the level of successful attribution, as this significantly shortens the analysis phase and, in real-world situations, leads to faster responses and actionable intelligence.”

Cunningham says that CPRI plans to further study this question of attribution, as well as when and how to respond to attacks, and he anticipates additional “war games” sponsored by the institute. “You could easily have an exercise around those kinds of issues — exploring how businesses could cooperate with law enforcement or intelligence agencies and helping CISOs and company leadership understand how to successfully do so.” He also hopes to make future events more hands-on, with real-time polling, computer-based participation, and additional stakeholders, such as insurance companies and law firms.

“We definitely will be holding more events like this,” he says. “We’ll look at hypothetical scenarios like how do you deal with a situation where, based on an attack, you learn something about the attack that likely will have major economic or national security implications.”

As George explains, “doing similar exercises in a corporate context within an organization is usually scripted and predictable.” He valued the CPRI event because it was “unique in that it was cross sector and also incorporated cyber and physical security threats on a larger scale.”

— Shani Murray